Tomorrow, Tomorrow, Insha-Allah

A true story by Sara Cheikh

Out now!

The story told in the book gets complemented by this audiovisual online archive.

ONE MONTH

IN MHEIRIZ

Chapter 03ONE MONTH IN MHEIRIZ

[ENG] I hear the sound of a car approaching and try to guess its model and colour, which is my new hobby for the week. "Blue Land Rover Santana," I say to myself mentally.

The sound of a 4×4 that has lived through a war is getting closer and closer. I lean out of the tiny kitchen window to validate my prediction. Ships, it's a white Santana. Just between you and me, guessing that it was a Santana doesn't have much merit either: almost 80%, an estimated figure whose source is my anecdotal experience, validated by anyone living in Western Sahara, of the cars circulating in the liberated territories and in the Tindouf camps are Land Rover Santanas.

Originally used by Spanish forces in Western Sahara, Land Rover Santanas were manufactured by Santana Motor in Linares, Jaén. This company began by assembling sets of British Land Rover parts and then made modifications to the design until it introduced its own models. After the 1976 Madrid Agreement, under which Spain ceded the territory of the Sahara not to its legitimate inhabitants, but to Morocco and Mauritania, the Saharawi People's Liberation Army turned the Land Rover Santana into its "battle camel" to launch attacks against the invading forces and thus recover a large part of its territory. Since then, this car has become a symbol of struggle and resistance for the Saharawi, thanks to its crucial role during the war, as well as its endurance and performance.

While it's not the most comfortable car for long-distance travel, it is one of the easiest to repair. Chances are your head will hit the roof with every pothole but, if it ever breaks down, you'll be able to fix it with some mechanical know-how and a date pit.

[ESP] Oigo el ruido de un coche acercarse e intento adivinar su modelo y color, que es mi nuevo pasatiempo de la semana. «Land Rover Santana azul», me digo mentalmente.

El sonido a 4×4 que ha vivido una guerra se oye cada vez más cerca. Me asomo por la minúscula ventana de la cocina para validar mi predicción. ¡Mierda!, es un Santana blanco. Entre tú y yo: adivinar que era un Santana tampoco tiene mucho mérito: casi el 80 % —cifra estimativa cuya fuente es mi experiencia anecdótica validada por cualquier persona que vive en el Sáhara Occidental— de los coches que circulan en los territorios liberados y en los campamentos de Tinduf son Land Rover Santana.

Originalmente utilizados por las fuerzas españolas en el Sáhara Occidental, los Land Rover Santana eran fabricados por Santana Motor en Linares, provincia de Jaén. Esta empresa empezó ensamblando juegos de piezas británicas para luego ir introduciendo modificaciones en el diseño hasta presentar modelos propios. Después del acuerdo de Madrid de 1976 —por el que España cedía el territorio del Sáhara no a sus legítimos habitantes, sino a Marruecos y Mauritania—, el Ejército de Liberación Popular Saharaui convirtió al Land Rover Santana en su «camello de batalla» para lanzar ataques contra las fuerzas invasoras y recuperar, así, gran parte de su territorio. Desde entonces, este coche se ha convertido en un símbolo de lucha y resistencia para los saharauis gracias a su papel crucial durante la guerra, al igual que por su resistencia y rendimiento.

Aunque no es el vehículo más cómodo para viajar largas distancias, sí que es de los más fáciles de reparar. Lo más probable es que tu cabeza golpee el techo con cada bache, pero, si alguna vez se estropea, vas a poder arreglarlo con conocimientos medios en mecánica y el hueso de un dátil.

The sound of a 4×4 that has lived through a war is getting closer and closer. I lean out of the tiny kitchen window to validate my prediction. Ships, it's a white Santana. Just between you and me, guessing that it was a Santana doesn't have much merit either: almost 80%, an estimated figure whose source is my anecdotal experience, validated by anyone living in Western Sahara, of the cars circulating in the liberated territories and in the Tindouf camps are Land Rover Santanas.

Originally used by Spanish forces in Western Sahara, Land Rover Santanas were manufactured by Santana Motor in Linares, Jaén. This company began by assembling sets of British Land Rover parts and then made modifications to the design until it introduced its own models. After the 1976 Madrid Agreement, under which Spain ceded the territory of the Sahara not to its legitimate inhabitants, but to Morocco and Mauritania, the Saharawi People's Liberation Army turned the Land Rover Santana into its "battle camel" to launch attacks against the invading forces and thus recover a large part of its territory. Since then, this car has become a symbol of struggle and resistance for the Saharawi, thanks to its crucial role during the war, as well as its endurance and performance.

While it's not the most comfortable car for long-distance travel, it is one of the easiest to repair. Chances are your head will hit the roof with every pothole but, if it ever breaks down, you'll be able to fix it with some mechanical know-how and a date pit.

[ESP] Oigo el ruido de un coche acercarse e intento adivinar su modelo y color, que es mi nuevo pasatiempo de la semana. «Land Rover Santana azul», me digo mentalmente.

El sonido a 4×4 que ha vivido una guerra se oye cada vez más cerca. Me asomo por la minúscula ventana de la cocina para validar mi predicción. ¡Mierda!, es un Santana blanco. Entre tú y yo: adivinar que era un Santana tampoco tiene mucho mérito: casi el 80 % —cifra estimativa cuya fuente es mi experiencia anecdótica validada por cualquier persona que vive en el Sáhara Occidental— de los coches que circulan en los territorios liberados y en los campamentos de Tinduf son Land Rover Santana.

Originalmente utilizados por las fuerzas españolas en el Sáhara Occidental, los Land Rover Santana eran fabricados por Santana Motor en Linares, provincia de Jaén. Esta empresa empezó ensamblando juegos de piezas británicas para luego ir introduciendo modificaciones en el diseño hasta presentar modelos propios. Después del acuerdo de Madrid de 1976 —por el que España cedía el territorio del Sáhara no a sus legítimos habitantes, sino a Marruecos y Mauritania—, el Ejército de Liberación Popular Saharaui convirtió al Land Rover Santana en su «camello de batalla» para lanzar ataques contra las fuerzas invasoras y recuperar, así, gran parte de su territorio. Desde entonces, este coche se ha convertido en un símbolo de lucha y resistencia para los saharauis gracias a su papel crucial durante la guerra, al igual que por su resistencia y rendimiento.

Aunque no es el vehículo más cómodo para viajar largas distancias, sí que es de los más fáciles de reparar. Lo más probable es que tu cabeza golpee el techo con cada bache, pero, si alguna vez se estropea, vas a poder arreglarlo con conocimientos medios en mecánica y el hueso de un dátil.

Extract from the book / Extracto del libro

From left to right: My aunt Nayat, my grandmother Noa and my mother. Smara camp in Tindouf, Algeria, 1992.

From left to right: My aunt Nayat, my grandmother Noa and my mother. Smara camp in Tindouf, Algeria, 1992.

My dad with me and my siblings in a trip to Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, 1996.

My aunt Selekha and Noa in Mheriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, 2004.

My aunt Selekha and Noa in Mheriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, 2004. Noa in one of the few photos she let us do. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, 2017.

Noa in one of the few photos she let us do. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, 2017. From left to right: my aunt Nayla's cloth-wrapped car, my mother's gray car, the kitchen, grandma Noa's room, the middle room with Noa junior peeking through the door, my aunt Selekha's green car and the last room where Malik and Sidi Buya sleep. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

From left to right: my aunt Nayla's cloth-wrapped car, my mother's gray car, the kitchen, grandma Noa's room, the middle room with Noa junior peeking through the door, my aunt Selekha's green car and the last room where Malik and Sidi Buya sleep. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020. Noa junior in front of my mother's car and kitchen. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020

Noa junior in front of my mother's car and kitchen. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020 From left to right: Beiba, Selekha, Gbnaha with Noa Junior, Sidi Buya, Malik and Hezman in front of Noa's room. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

From left to right: Beiba, Selekha, Gbnaha with Noa Junior, Sidi Buya, Malik and Hezman in front of Noa's room. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

My father in his tourist attire (left) and already acclimatized to desert fashion (right). Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

One of the workers building a wall in front of the kitchen. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

One of the workers building a wall in front of the kitchen. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020. Brahim approaching the car, seconds before asking my mother for batteries for his radio. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

Brahim approaching the car, seconds before asking my mother for batteries for his radio. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

Gbnaha and my finger in front of Abdalahi's family tent. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

The cat, “Mise”. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

The cat, “Mise”. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020. My cousin Muhamad in the middle, me in purple, my sister Nayat in pink, my cousin Khalil squatting with a piece of bread in his hand, my brother Musa also squatting in the right, and the pink backpack my cousin Nazah gave me in the center. Smara camp in Tindouf, Algeria, 1995.

My cousin Muhamad in the middle, me in purple, my sister Nayat in pink, my cousin Khalil squatting with a piece of bread in his hand, my brother Musa also squatting in the right, and the pink backpack my cousin Nazah gave me in the center. Smara camp in Tindouf, Algeria, 1995.

My father (left) with Ahmed Sid Ali and one of his sons riding on his car moments before leaving Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020.

My father (left) with Ahmed Sid Ali and one of his sons riding on his car moments before leaving Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, March 2020. My sister Nayat (left) in front of Noa's tent, near where I hid the dates. Smara camp in Tindouf, Algeria, 1996.

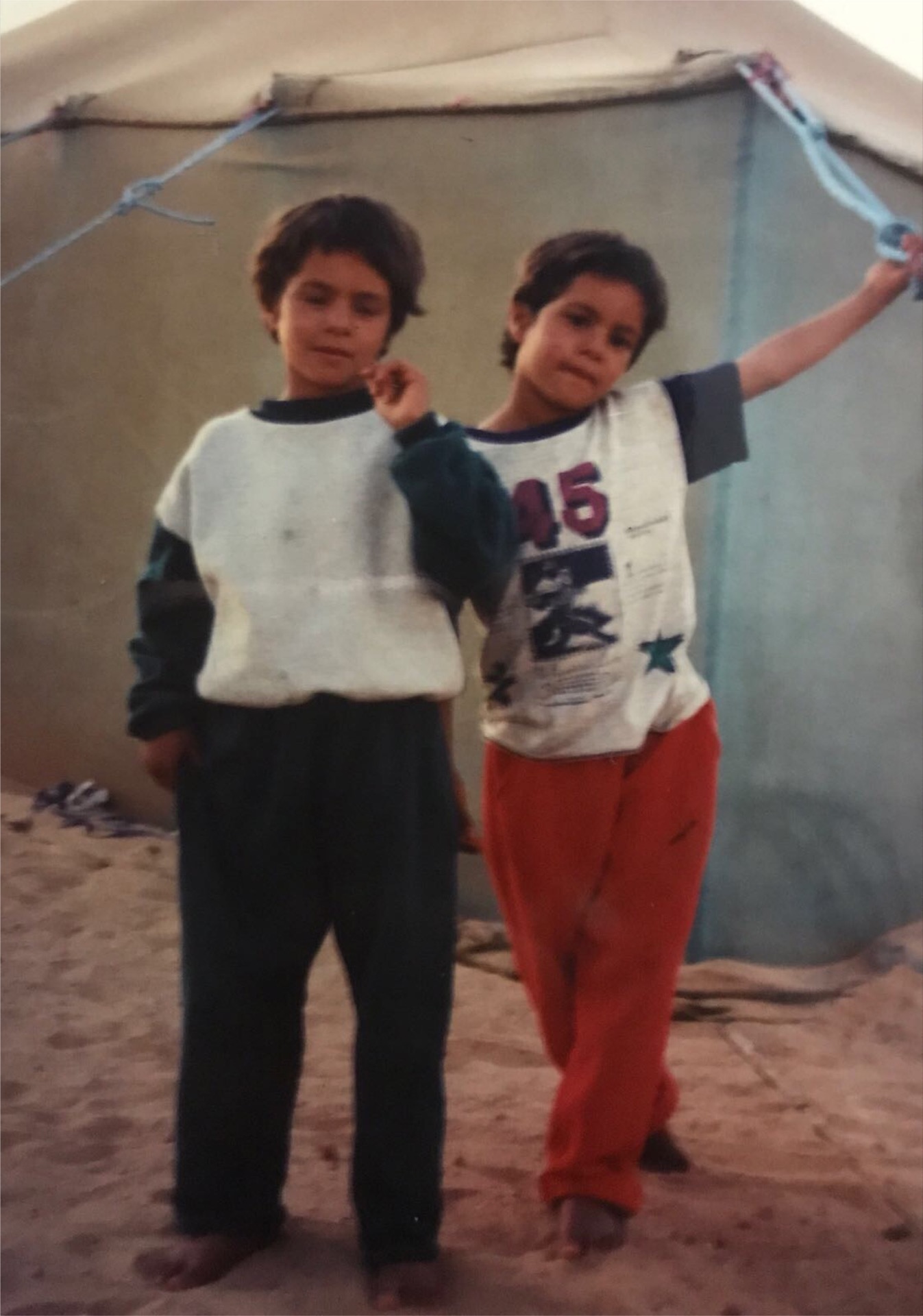

My sister Nayat (left) in front of Noa's tent, near where I hid the dates. Smara camp in Tindouf, Algeria, 1996. My sister (right) and I at the time when we played passive nouch. Smara camp in Tindouf, Algeria, 1999.

My sister (right) and I at the time when we played passive nouch. Smara camp in Tindouf, Algeria, 1999.

On the left, my mother and Beiba doing a tea break during our first trip to find internet connection. On the right, my father during the same trip in his prayer break. Free territories of WesternSahara, April 2020.

On the top, Beiba in one of the many photos she has asked me to take, and on the bottom she is asking me to take more photos of her while complaning about not having battery on her phone. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, April 2020.

My mother posing in front of Noa's room before going to fetch water from the well. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, April, 2020.

My mother at the boarding school where she started studying in Algeria, 1979

![]() My mother in the second row on the left during a class in the refugee camps, Tindouf, Argelia, 1984.

My mother in the second row on the left during a class in the refugee camps, Tindouf, Argelia, 1984.

![]() My mother with her teacher during her scholarship years in Vienna, Austria, 1987.

My mother with her teacher during her scholarship years in Vienna, Austria, 1987.

![]() Article about my mother and the situation in Western Sahara at the time my mother was studying pedagogy in Vienna, Austria. 1988

Article about my mother and the situation in Western Sahara at the time my mother was studying pedagogy in Vienna, Austria. 1988

![]()

![]()

My mother handing out brochures on Western Sahara in Vienna, Austria. 1988

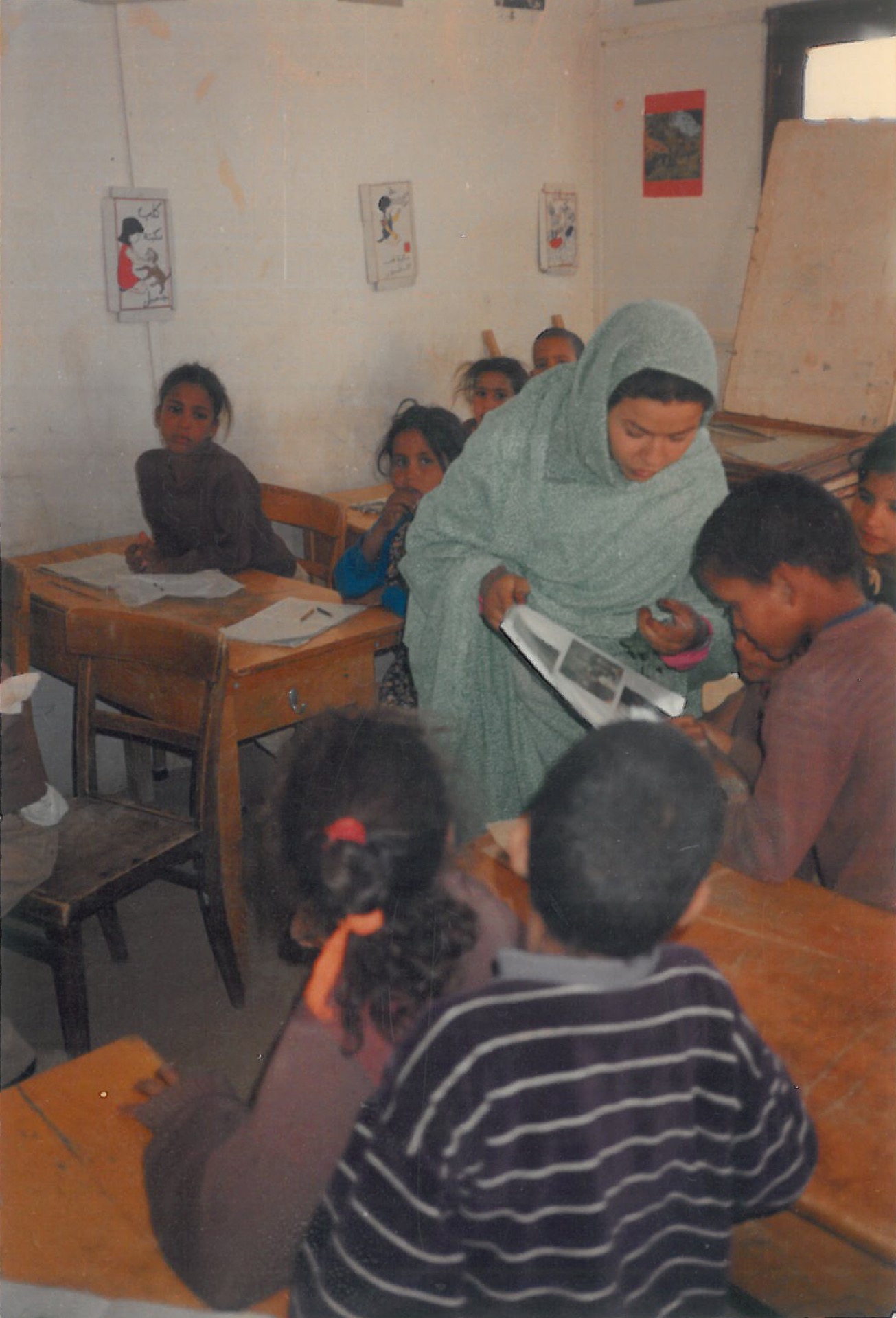

![]() My mother working as a primary school teacher in the Asmara camp in Tindouf, Algeria. 1989

My mother working as a primary school teacher in the Asmara camp in Tindouf, Algeria. 1989

![]() My mother speaking about Western Sahara to a group of Palestinians in Berlin, Germany, 1988.

My mother speaking about Western Sahara to a group of Palestinians in Berlin, Germany, 1988.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Some of the drivers who have agreed to be photographed with their Land Rover Santana. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, April, 2020.

Some of the drivers who have agreed to be photographed with their Land Rover Santana. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, April, 2020.

My mother in the second row on the left during a class in the refugee camps, Tindouf, Argelia, 1984.

My mother in the second row on the left during a class in the refugee camps, Tindouf, Argelia, 1984. My mother with her teacher during her scholarship years in Vienna, Austria, 1987.

My mother with her teacher during her scholarship years in Vienna, Austria, 1987. Article about my mother and the situation in Western Sahara at the time my mother was studying pedagogy in Vienna, Austria. 1988

Article about my mother and the situation in Western Sahara at the time my mother was studying pedagogy in Vienna, Austria. 1988

My mother handing out brochures on Western Sahara in Vienna, Austria. 1988

My mother working as a primary school teacher in the Asmara camp in Tindouf, Algeria. 1989

My mother working as a primary school teacher in the Asmara camp in Tindouf, Algeria. 1989 My mother speaking about Western Sahara to a group of Palestinians in Berlin, Germany, 1988.

My mother speaking about Western Sahara to a group of Palestinians in Berlin, Germany, 1988.

Some of the drivers who have agreed to be photographed with their Land Rover Santana. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, April, 2020.

Some of the drivers who have agreed to be photographed with their Land Rover Santana. Mheiriz, liberated territories of Western Sahara, April, 2020.